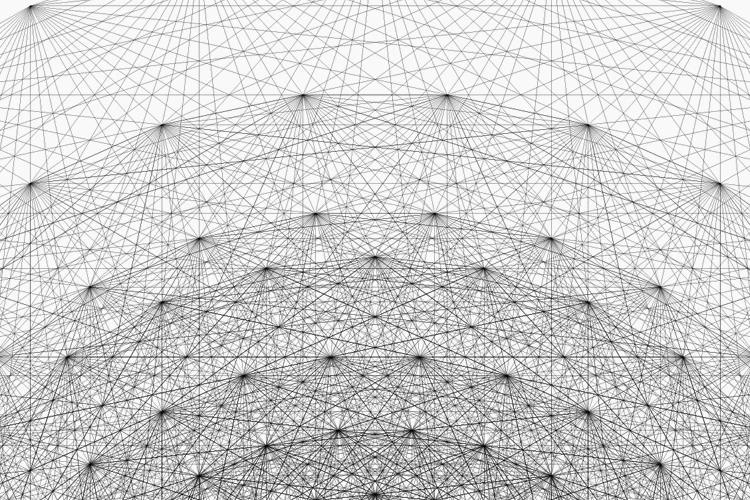

The walls of Peter Crnokrak’s home-studio in Hackney are covered with work. From roughs, concepts and runouts to logoforms, finished posters and literature, it’s evidence of an accomplished and extensive body of both commercial and self-initiated graphic design. Yet out of all of it, my attention is drawn, irresistibly, to a single, centrally placed piece. Titled Real Magick in Theory and Practise, it’s a visual representation of the 4_21 polytope, which is said to explain the workings of the universe. It’s one of several large, intricate posters that have attracted considerable praise and attention for Crnokrak over the past four years, and standing face to face with the work, it’s immediately evident that when it comes to his data visualisations, the accolades haven’t been misplaced.

It’s also immediately obvious that data visualisation isn’t the only thing at which he excels. Crnokrak has squeezed a lot into his seven years as a practising graphic designer—since gaining his design degree in 2004, he’s worked on two continents, both as a solo practitioner and as a member of several respected studios, achieved a fellowship at the RSA and been recognised with awards from organisations as diverse as the AIGA and the National Science Foundation. It’s only been in the past two years, since he founded solo practice The Luxury of Protest, that data visualisation has become a prominent feature within his body of work, which still encompasses the commercial identity, literature and poster design that he’s honed over the course of his career. Talking to him today, it’s clear that he’s relished every second of all of it—pleased, undoubtedly, to find himself finally settled in a career he finds creatively fulfilling.

Crnokrak’s professional life did not begin in the design world. Born in Croatia and raised in Canada, he initially studied biology, pursuing an academic career which led him through a master’s and PhD to a research fellowship at the University of Toronto, working in the eld of quantitative genetics—“in simplest terms, the study of nature versus nurture,” he explains helpfully. Yet despite his successful scientific career, the design profession had long held a certain allure.

“I always revered designers, idolised them even,” he confesses. “I thought they were these amazing, enigmatic creatures—their ability to combine beauty, logic and functionality was something that fascinated me. I was halfway through my PhD when I realised I wasn’t on the right path and that design was something I wanted to pursue, but the momentum of my research career made it difficult to break away.” It was in 2002, six years after his initial, inconveniently timed revelation, that Crnokrak finally made the decision to abandon the sciences in favour of design. He and his wife, Karin von Ompteda—a fellow biologist with similar designerly leanings—left their research positions behind to start over in the design world. As she puts it, “We jumped off a cliff, holding hands.”

Their peers within the research community might have been puzzled by the departure, but for Crnokrak there’s no question that it was the right thing to do. “Quitting my research career was the best decision I ever made,” he expounds. “I’m a big proponent of quitting—I think quitting is a wonderful thing.” After graduating with a degree in visual design, Crnokrak began working freelance in Canada under the moniker ± (plusminus), developing a reputation for politically motivated, self-directed work that he would build on in later experiments with data. Determined to continue to grow as a designer, it wasn’t long before he began approaching studios in New York City, keen for a change of pace and the input of others, and he soon accepted a position at full-service agency The Apartment (although a simultaneous offer from Wolff Olins made the decision difficult, he confides), and found himself immediately at home within their studio culture, working alongside architects and interior designers on everything from conceptual architectural visualisations to the agency’s own identity and collateral. “Everyone at The Apartment was like a family,” he reminisces. “It didn’t feel like a job—even when I was working eighteen-hour days, I just didn’t want to go home.”

If Crnokrak’s time working freelance had allowed him to develop a socio-political position and minimal, feminine aesthetic within his work, it was his time at The Apartment that nurtured the consistent, integrated approach evident within the client-led commissions in his current portfolio. An example is his design for soon-to-open New York nightspot The Elevens—originally a straightforward identity job, he soon evolved the project to encompass everything from the logoform to the club’s interiors and signage. To this day, he still prefers to work with a client from the conception of a project to its completion, eschewing the here-and-there contributions of a more traditional freelance career.

The Apartment was also responsible for his eventual move to Britain, a place he’d longed to live since adolescence: “When I was fifteen and heard The Smiths for the first time, I immediately thought ‘I must go to mecca’.” The intention was to establish a London office for the agency, but after several months Crnokrak cut ties and set out in search of another studio. “Being separate from the studio environment, but still involved, wasn’t working for me,” he explains. “But I wasn’t ready to work alone yet—London’s a tough city, and it took a while to adjust.” A stint working with Nick Bell naturalised him to the capital’s design culture, though, and soon it was time for yet another change of tack. A private commission for French-film channel Cinémoi finally tempted Crnokrak away from collaborative, studio-based work and spurred him on to set up alone. He established The Luxury of Protest in 2009, placing a more equal emphasis on the self-directed and commercial sides of his practice. The change allowed him to pursue his interest in critical and politically focused projects—and, of course, to devote more time to those entrancing visualisations.

It might come as a surprise to hear that data visualisation is something that Crnokrak once made a concerted effort to avoid. “I shunned anything even remotely science-related in my work for a long time,” he reflects. “After working in the sciences for so long, I wanted to focus on becoming a different kind of person. I was worried I’d end up in this weird middle ground, halfway between science and design. The clean break made me a better designer.”

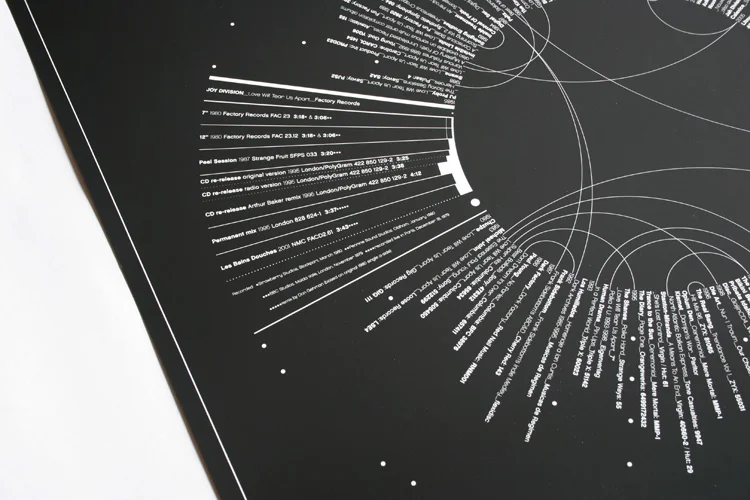

Although he’d produced politically motivated posters throughout his design career, Crnokrak’s first foray into data visualisation didn’t come until 2007, and was born of an interest in a decidedly unscientific topic—Joy Division. He’d amassed an enormous list of cover versions of Love Will Tear Us Apart, collected in an Excel document along with a range of ancillary information. “I looked at the file and realised I’d created a data set,” he explains, “and I decided to create a visualisation just for the hell of it.”

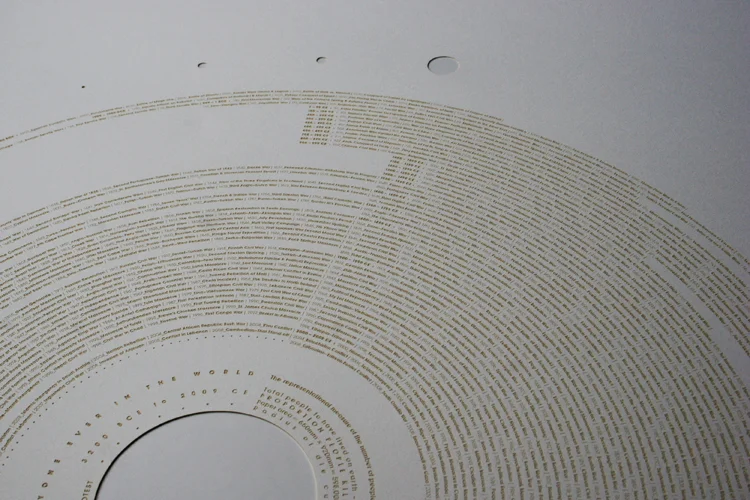

The resulting poster was the catalyst for a chain reaction which brought him back towards the scientific roots he’d been so keen to abandon. Crnokrak’s subsequent visualisations have interpreted data relating to everything from quantum physics to geopolitics, marrying immensely complex sets of information with a sensitive, minimalist design sensibility to stunning effect. Both the research and the actual creation of these posters can be immensely time-consuming for Crnokrak, with the recently completed visualisation Everyone Ever in the World taking three months just to collect the data. The finished poster is a visual comparison between the total number of people who have ever lived and the number killed in conflicts since records began. “The data collection for that one was both disarmingly simple and cripplingly difficult,” he recalls. “I hesitated to start it because I knew how much work would be involved. Also, I wondered whether anyone would actually be interested—or whether it was just obsessive ‘design wanking’.”

There’s definitely an obsessive streak within Crnokrak’s self-initiated work; it sometimes seems like he enjoys making things difficult for himself. Take Real Magick, for example—every one of the innumerable points within the visualisation was placed manually in Illustrator by Crnokrak, and each individual poster painstakingly finished with hand-applied 23-carat gold dust.

It all stems from a fixation with both accuracy and craftsmanship, the former no doubt being a throwback to his earlier research career. The latter has been facilitated by his move to Britain, where he’s found printers to be infinitely more accommodating of a designer’s perfectionism and foibles.

“When I was working in the USA, the printers there would have me banging my head against the wall,” he recalls with a wince. “For them, it was all about speed, but Britain’s been a revelation in terms of the pride that printers take in traditional craftsmanship.” It’s no coincidence that Crnokrak’s self-directed data visualisations have become a prominent part of his work since he established The Luxury of Protest—he’s clearly more at home now he’s working alone, with the exception of several recent projects produced in collaboration with his wife, Karin, now a PhD candidate in typography at the Royal College of Arts. “I don’t think I would ever go back to working in a studio environment,” he asserts. “I’d rather pull my own teeth out.” Perhaps it’s his devotion to the idea of designer as author that’s set him in such good stead for solo work—he’s an enthusiastic advocate of self-directed practice, and his pursuit of personal and particular career goals doesn’t really lend itself to company.

Crnokrak is keen to see the value of self-initiated, critical design practice increase among both designers and clients, and seems mystified by the lack of acceptance of this way of working among his peers. “It amazes me that some still seem to think that graphic designers don’t have the expertise to take on these kinds of projects,” he says. “I’m not an anomaly because of my background in science—so many graphic designers could accomplish this kind of work. There’s a bizarre inertia amongst visual designers, with many unwilling to accept that taking on technically complex subject matter or a critical approach might be a good thing.” For his part, he’s held several critical visualisation workshops with Karin both at the RCA and abroad, advising and encouraging a new wave of practitioners in their exploration of information design as a vehicle for both interpretation and critique.

Though he believes that designers still require some persuasion to accept this kind of practice more readily, his clients seem to have little problem doing so—in fact, quite the contrary. He’s often commissioned to apply his approach to data to everything from magazine infographics to mobile phone identities, which is testament to the appeal of the work’s aesthetic, conceptual grounding and critical position.

Curiously, however, he’s never been contacted by a member of the scientific community to put his skills to use on their research. “The communication channels just aren’t there,” he explains. “People within the sciences don’t normally encounter the design world and most probably aren’t aware of the work that I, or other designers, are doing in this area.”

In spite of the attention and admiration his visualisations have attracted, Crnokrak is keen not to let them define him. “Visually, and stylistically, my client-led work is no different from what I do personally—it’s pared-down, and it’s focused. Ultimately, it all flows into one,” he asserts. “Definitions can be useful now and again, but mostly when you’re in the thick of it you don’t bother with them. If you’re worrying about how to define yourself as a designer, you’re not working hard enough. What’s most important is to create a body of work that represents your individual interests, preferences and tastes.”

It’s certainly true that it’s hard to look at Crnokrak’s work as a whole without acquiring a distinct impression of what the man himself is actually like—his own personality is woven so closely within it as to be intrinsic, and Crnokrak the scientist is still as evident as Crnokrak the designer. Contrary to his earlier concerns, his experimentation with data and scientific subject matter have left him not in an ill-defined middle ground between science and design but in an advantageous position, armed with assets developed in two wildly different careers. Would he have arrived at the same results had he not spent so long in the sciences? It’s impossible to say, but it seems unlikely that they’d be as nuanced or appear so effortless.

Fittingly, it’s his wife, Karin, who can provide the most succinct summing up of both the man and his work. “Peter believes in beauty as the conveyor of complex ideas and difficult truths,” she asserts. “In so doing he communicates with people, and makes a connection on a personal level—you get to know Peter when you look at his work, and you learn something through a strange, visual conversation.” Strange though that conversation may be, there’s little doubt that, through the design he’s produced during his relatively short career, Crnokrak’s speaking in a voice that’s unique, persuasive and powerful.

Originally published in Grafik magazine, issue 190. Images © The Luxury of Protest/Peter Crnokrak.